In a previous article, we looked at the somewhat controversial development of “camming devices”, and highlighted some ways that the patent system could have been more effectively utilised. This time we are looking at another category of climbing equipment, belay devices, and how they have been effectively protected using patents.

Belay devices are not used directly by the climber but are instead used by their climbing partner (“belayer”) located at the other end of the rope. The belayer’s task is to feed out or take in rope while the climber is ascending but be ready to catch the climber on the rope if they fall. This is not as simple as holding onto the opposite end of the rope; for both safety and comfort, belayers use specialist belay devices that use the friction of the rope to arrest the climber’s fall. The way in which these belay devices utilise mechanical advantage can be very interesting (and for this reason have even been the subject of UK patent examination papers).

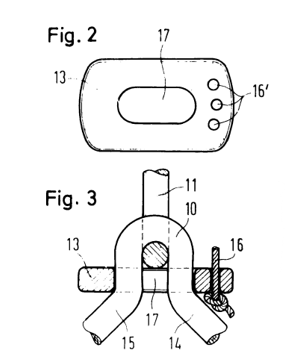

One of the earliest examples of a specialised belay device is the Sticht plate (named after inventor Fritz Sticht), which was patented in Germany in the 1970s (DE1927155B2). Although devices resembling the original Sticht plate are rarely seen nowadays, variants of it (known as “tubular” belay devices) are still widely used. In fact, the earliest tubular belay device (the “Latok Tuber”) was invented in 1983 by Jeff Lowe, the brother of one of the protagonists of the camming device story, Greg Lowe!

Up to this point, all belay devices on the market were “passive” devices, where the belayer needed to hold the rope in the correct position manually to allow or prevent movement of the rope through the device.

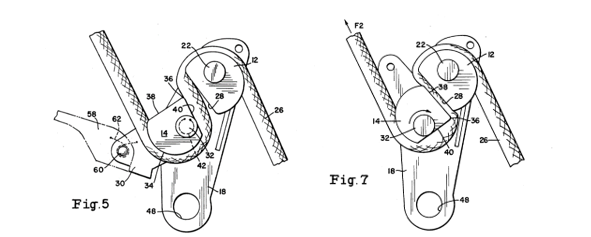

However, in 1989 the French equipment manufacturer Petzl® filed a patent application for an “assisted” belay device. This device (called the “GriGri”) differed from the existing passive devices in that a sudden movement of the rope (i.e. caused by a fall) would automatically lock the rope within the device. The key feature of the device that enables this was a spring-loaded cam (14) movable between an open position (see Fig. 5) where the rope can move freely through the device and a closed position (see Fig. 7) where the rope is tightly pinched to prevent further movement. Once in the closed position, the climber could remain suspended on the rope with minimal effort from the belayer. The cam could then be easily returned to the open position by moving a lever (58), which allowed a climber to be gently lowered after a fall.

As a result of the above improvements to convenience and safety, the GriGri became a very popular belay device, and to many people it is synonymous with assisted belay devices as a whole. However, a patent only grants its proprietor a monopoly on the technology for 20 years, which meant that protection for the original GriGri expired in 2010.

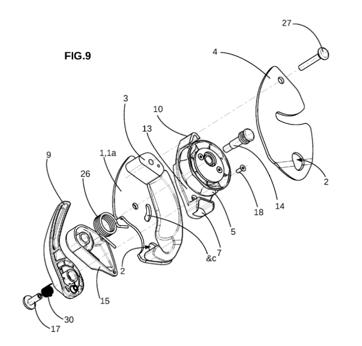

It is perhaps no coincidence that Petzl filed a further family of patent applications around 2010 (e.g., EP2301631B1), coinciding with the release of the second-generation GriGri in 2011 (the “GriGri2”). The updated device improved upon the operation of the rope release lever so that it was even easier for the user to control the release of the rope following engagement of the locking mechanism. Although these improvements would certainly have enhanced the functionality of the product itself, doing so also ensured that Petzl could keep its current commercial product covered by a patent.

Particularly for mechanical products that can be easily reverse engineered, having a patent in force covering the technology is critical to prevent competitors from making unauthorised copies of the devices. If a third party were able to manufacture copies of the devices at a lower cost, not only would this undercut the market for the original product (thereby siphoning off a portion of the revenue), but it could also dilute the value of the brand, and possibly present a severe safety concern if the third-party products did not function as well as the original.

Although the patent application for the GriGri2 related to smaller improvements to the original mechanism, Petzl would go on to file further patent applications that covered more significant developments. In 2017, Petzl released the “GriGri+”, which included further features such as an anti-panic function, and different operating modes, covered by EP3056248B1 and EP3124081B1 respectively.

More recently in summer 2024, Petzl released a new product, the “Neox”. This device features a rotating wheel to make it easier to feed out rope, thereby making it a particularly attractive option for sport climbers. A patent application covering its device was first filed in 2021 and is due to be granted in Europe shortly.

As demonstrated above, Petzl is not only an innovator within the field of belay devices but also appears to understand the benefits of the patent system for protecting its R&D investment, maintaining brand value, and retaining a strong position within the market. For this reason, Petzl remains a go-to brand for assisted belay devices long after expiry of its original patent.

If you have an invention that you would like to protect, or if you would like to discuss how patents could be used more effectively within your business, please email us: gje@gje.com.