The EPO Boards of Appeal have been developing a useful body of case law in the business method space in which the concept of a ‘notional business person’ is introduced in order to help with the task of determining just what can and cannot be included in the requirements specification given to a skilled person to implement. (See our previous article on this subject here). In decision T 1749/14 the Board confirmed that the ‘how’ of a technical implementation cannot be supplied by the business person and also indicated that the creation of new protocols and corresponding modification of existing hardware is beyond the routine knowledge of a skilled person, at least where technical considerations are involved in these modifications.

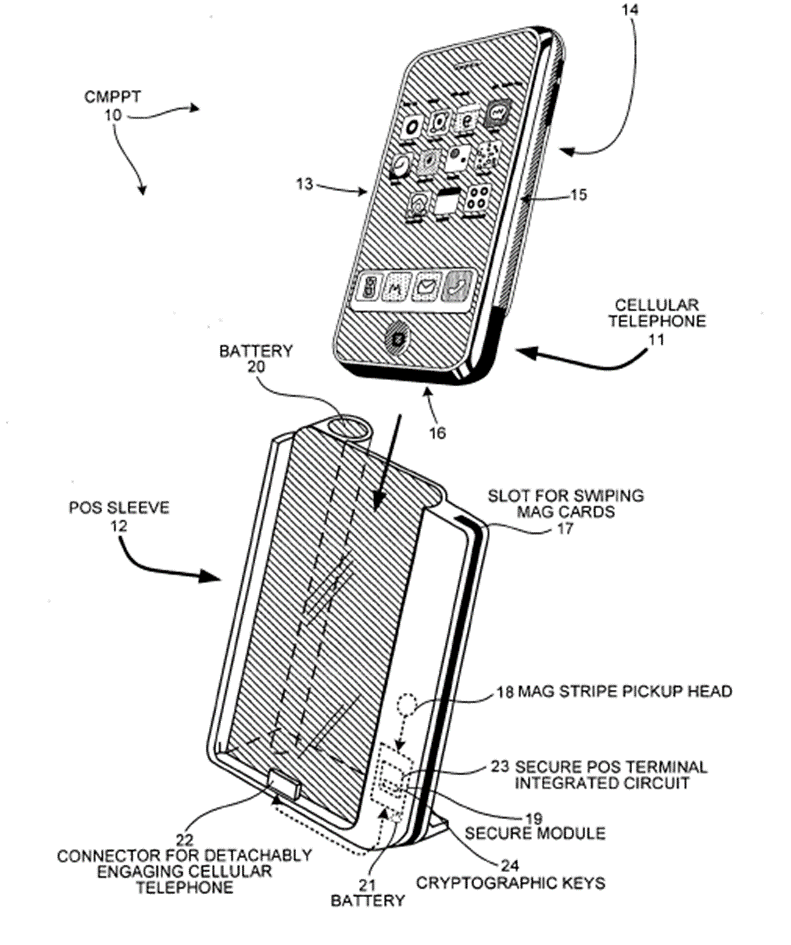

T 1749/14 concerns an invention having a customer mobile personal point-of-sale terminal (‘CMPPT’) comprising a mobile phone and a point-of-sale terminal attachment mechanism (see Fig.2 of the patent application, reproduced below). The CMPPT stores personalised information relating to a specific customer, including encryption keys for communicating securely with a financial transaction verification entity. The CMPPT participates in a transaction by sending customer account information from the mobile phone to the financial transaction verification entity. The phone is personalised in the sense that it includes encryption keys and sensitive data corresponding to one particular customer only.

The technical effect of this arrangement was determined to be enabling a transaction to proceed without merchant-operated hardware having access to sensitive customer information, this instead being held in the mobile phone, such that sensitive customer information cannot be stolen by a fraudulent party using a compromised merchant terminal.

The closest prior art (D1) disclosed a mobile POS terminal comprising a mobile phone and a merchant-operated docking module. At this high level the similarities with the CMPPT are easy to see – D1 includes a mobile phone and POS terminal attachment mechanism in the form of the docking module. However, looking into the detailed operation of D1’s apparatus revealed that the mobile phone in D1 was a ‘generic’ phone that was present only to provide a data connection. The docking module handled all of the transaction-related operations, meaning that the customer PIN and account number were accessible to the merchant-operated docking module during a transaction.

Splitting up the CMPPT into a customer-controlled portion and a merchant-controlled portion was found to be a technical feature that gave rise to the technical effect outlined above. The Board found that D1 suffered from exactly the problem the invention attempts to solve – namely that sensitive customer information is accessible to a merchant-operated piece of hardware in D1. Thus, no hint towards this solution was found in D1 and accordingly the invention was found novel and inventive over D1.

In reaching its decision the Board considered what contribution the business person may have made to the invention, if any, so as to properly formulate any requirements specification that was to be given to the skilled person to implement. The Board commented that “in the present case the notional business person might come up with the abstract idea of avoiding the customer having to provide PIN and account information to the merchant. Even when considering this to be an abstract business concept for carrying out POS transactions, it cannot however be convincingly argued that it would be sufficient to implement this idea on a standard general purpose mobile POS terminal infrastructure as known from D1 with standard programming skills”.

The Board also found that the creation of the CMPPT was beyond routine work for the skilled person, stating:

“[The invention] requires a new infrastructure, new devices and a new protocol involving technical considerations linked to modified devices and their capabilities as well as security relevant modifications of the transfer of sensitive information using new possibilities achieved by the modifications to the mobile POS infrastructure… [this] goes beyond what the notional business person knows, but rather concerns technical implementation details (how to implement) which are more than a straight-forward 1:1 programming of an abstract business idea.”

This is a helpful clarification of the abilities and knowledge of the business person and also useful guidance as to the bounds of ‘routine programming’ by a skilled person. In particular, the business person may provide the initial motivation to develop a technical system but cannot give guidance on how the system will operate. Creation of a new protocol is beyond ‘routine programming’, as is modifying the operation of an existing device such that it operates in a new manner, at least in the case where there are underlying technical considerations in these modifications (in this case, security considerations).

It is also helpful that the Board found the CMPPT to be a ‘new device’. The phone within the CMPPT differed only D1’s phone in how it was programmed; it is not ‘new hardware’ in the physical sense. The principles set out in this decision should therefore be extendible to the logical separation of data generally, where such separation is motivated by a technical consideration such as data security.

Another point of note is that the concept of ownership is invoked here – the idea that the entity that has control of a particular component is of technical relevance and usable to show a technical effect. The claims considered by the Board used language such as ‘customer mobile personal point-of-sale terminal’, with the word ‘customer’ having the effect of assigning ownership of this hardware. The customer is a non-technical business entity, so prior to this decision including such labelling in claims may have seemed unnecessary or perhaps even unhelpful. However, one wonders if a claim directed to ‘a POS terminal’ or similar would have been found by the Board to credibly achieve the technical effect discussed above. It thus seems that it can be advantageous to use specific labels such as ‘merchant server’, ‘customer mobile device’, etc. in claims where security considerations bring component ownership into the technical domain.

If you would like to discuss any of the points raised in this article, please contact us at: gje@gje.com.

Fig. 2 of the patent application showing CMPPT