Registered designs exist to protect the aesthetic appearance of products, and as such European Community design law was drafted so as to exclude protection for certain aspects of appearance that would allow for monopolies to be created around purely functional designs. Recent decision T-515/19 by the General Court considered an exception to one of these exclusions, and appears to build on the protection available to the designers of modular systems.

In short, this decision suggests that the designers of modular systems may be able to obtain greater protection for their products. It was previously assumed by many that the elements which enable interconnectivity of modular systems must still have some sort of aesthetic consideration in order to benefit from Community design protection. However, in T-515/19, the General Court seems to sanction the protection of all interconnection elements of modular systems, even those with purely technical considerations to their appearance.

Designs dictated by their technical function

The legal backdrop to this case is Article 8 of the European Community design regulation, which seeks to exclude protection for designs dictated by their technical function.

Article 8(1) of the regulation sets out that a “design shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which are solely dictated by its technical function”. For a number of years, there were differing approaches to the application of this exclusion. In recent years, case law has seemed to settle the debate by backing the so-called “no-aesthetic-consideration” test, by which design protection will only be conferred if an aesthetic consideration contributed to the design of the feature.

Article 8(2) provides another exclusion, setting out that a “design shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which must necessarily be reproduced in their exact form” in order to be mechanically connected to another product so that either product may perform its function. This is the so-called “must-fit” exclusion, and aims to prevent companies from protecting proprietary connections and the like, so as to preserve the ability for products from different sources to be compatible with one another.

Finally, Article 8(3), which is the subject of the decision in question, states that “Notwithstanding [Article 8(2)], a Community design shall… subsist in a design serving the purpose of allowing the multiple assembly or connection of mutually interchangeable products within a modular system”. As noted in T515/19, this exception was incorporated into the Regulation on the basis that the mechanical fittings of modular products may constitute an important element of the innovative characteristics of modular products and present a major marketing asset, and therefore should be eligible for protection. In their decision, the Court explores how this exception to the exclusion should be applied.

The Decision

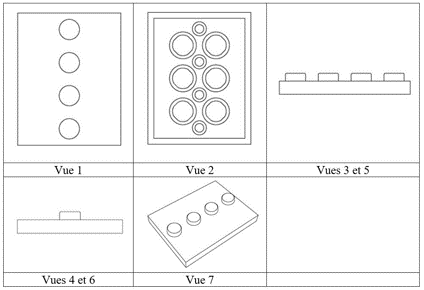

In February 2010, Lego A/S filed a Community design application with the following views.

The design was registered and published shortly thereafter, and it was not until 8 December 2016 that Delta Sport Handelskontor GmbH filed an application for a declaration of invalidity of the design. Delta Sport claimed that all the features of appearance of the product concerned by the contested design were solely dictated by the technical function of the product, and so were excluded under Article 8(1) of the Community design regulation. Lego countered that (i) the design included features which were based on aesthetic considerations and hence should not be excluded under Article 8(1), and (ii) the features which were purely based on technical considerations were interconnection elements which should benefit from the exception of Article 8(3).

The case eventually found its way to the General Court on appeal, and the Court ruled that the EUIPO had erred in declaring the design invalid under Article 8(1). The reasoning for the decision here was interesting, as the General Court stated that while the exception in Article 8(3) referred only to paragraph 2, the exception must shield a design from both paragraphs 1 and 2 if the design would otherwise fall within the exclusions of both of those paragraphs. The Court’s view was essentially that paragraphs 1 and 2 defined partially overlapping exclusions and that, in the absence of any indication to the contrary, Article 8(3) must apply where these exclusions overlap, or else it would be deprived of a substantial part of its effectiveness with respect to Article 8(2).

The key point in this General Court decision would seem to be that even if a feature of a design includes no aesthetic consideration, if the design is part of a modular system and the feature in question is an interconnection element which must be replicated in its exact form to function, then it may nonetheless benefit from the modular system exception of Article 8(3).

It ought to be emphasised, however, that the Court did not go so far as to decide whether the design in question does in fact meet the definition of a “modular product” and hence whether it benefits from the Article 8(3) exemption. It will be interesting to see how this aspect of the case develops.

Conclusion

In all, this decision is good news for the designers of modular systems, as they may now seek to protect the appearance of the features which enable interconnection between the parts of their product even without the need for aesthetic considerations in the conception of these elements. This opens the door to protection of essentially purely functional products using registered designs, provided they fall within this niche carved out for modular systems.

If you have any questions regarding the protection of your product using registered designs, then please find my contact details here, or contact us at gje@gje.com.