AI & IP Series

This is the first of a series of articles directed at all innovators using artificial intelligence to solve problems in healthcare. Our aim is to address some of the misconceptions we hear frequently around the protection of AI-based HealthTech inventions and to provide some practical guidance on the steps that should be taken to secure protection that supports your commercial aims and the wider adoption of your technology.

For those interested in pursuing protection for AI-driven HealthTech innovations, please contact medtech@gje to arrange a free IP consultation.

Part 1 “You can’t patent algorithms” – a guide to identifying and protecting AI inventions in Healthcare

This first article in the series introduces patent protection in the AI and HealthTech space and focusses on the question that we hear most often from those new to the patent system, namely – when is an AI technology patentable? We explain in simple terms how the patent office assesses patentability in this field and set out some of the common categories of AI inventions, with the aim of equipping innovators so that they can better identify their own patentable AI inventions.

The next article will go on to consider the less asked, but arguably more important question, “is patent protection the right option?”, and explain the crucial wider IP considerations necessary in developing an IP strategy in this field.

Machine learning inventions in healthcare

Generally, when the term “AI” is being used, particularly in a HealthTech context, it is most likely in reference to the use of machine learning (ML) – algorithms structured to progressively improve their performance at a particular predictive task performed on an input data set. The pace of innovation in this area has been rapid and we are advising on an increasingly diverse range of ML applications in health and care – from medical image processing and computer vision, the identification of biomarkers in patient data for diagnosis, drug discovery and development to the development of AI entities for managing mental health conditions. It is very difficult to identify areas of the current health and care system that these technologies will not shape in some way.

The European Patent Office has noted that the increase in patent filings relating to AI technologies has been almost five times greater than the average growth in patent applications across all fields.

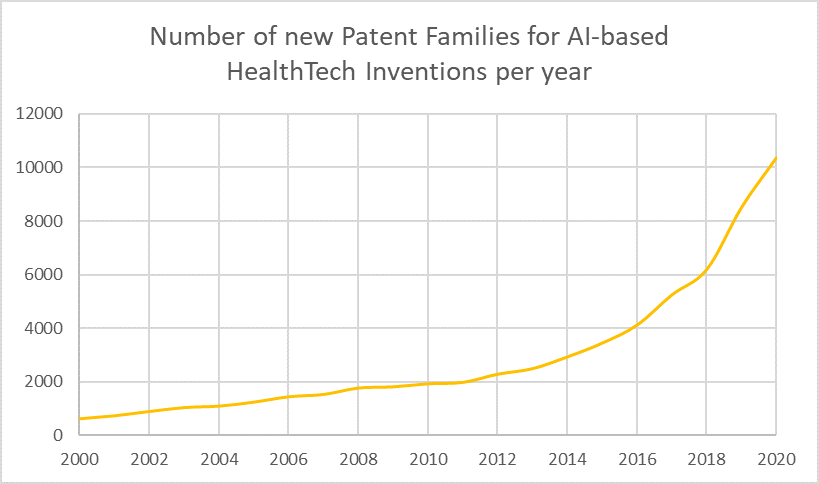

This rate of innovation is reflected in rapidly increasingly numbers of patent applications being filed for AI-powered HealthTech innovations, as illustrated in the graph below showing the number of new patent families (groups of patent applications focussed on a new invention) published each year. The European Patent Office has noted that the increase in patent filings relating to AI technologies has been almost five times greater than the average growth in patent applications across all fields.

The main motivations for seeking patent protection remain the same as other fields, although there are important technology-specific considerations. The primary driver is the possibility of securing a 20 year monopoly for a new AI technology in which patentees can control the use of the invention on their terms. Being early to file in a relatively young ML technology or area of application can allow for broad protection to be obtained which can secure a company’s market position for many years. We have recently seen the patent office acknowledge the patentability of claims of very broad scope in new applications of ML to healthcare problems.

For early-stage companies, an often quoted motivation is that the investors they have approached want to see protection in place. Indeed, a coherent IP strategy in this field is a key component of a successful funding round but, as we consider in our next article, it’s important to not be lead to filing purely by this kind of investor pressure. We have seen cases where patent protection is unlikely to be the best route to add value, despite being stated as a necessity by potential investors and so it is important to seek a view on this from the right IP advisor. A coherent IP strategy considers the full IP framework in the specific context of the particular business and technology and several of these alternative IP rights may be very relevant for innovations in this field. This is the subject of the next article in the series.

The different categories of AI invention

From the statistics above, it is clear that an increasing number of innovators are using the patent system to support the commercialisation of their AI technologies. Despite this, we frequently encounter misconceptions around what can be protected in this space and the best strategy for securing the most relevant protection. The following explains how the patent office – primarily focussed on the European Patent Office (EPO) – assesses AI inventions in Healthcare.

You do not need to have developed a new type of ML model to meet the requirements of patent protection – applying a known model in a new way or to solve a new problem is the most common type of AI invention that is patented.

The European Patent Office distinguishes between three types of AI invention:

(1) Core AI inventions relate to fundamental new advances in AI model architectures or techniques themselves. The innovation is within a new, general purpose AI technique, rather than the configuration or implementation of a technique for any one application. These are the hardest type of AI inventions to protect as they often fall close to the patent office’s restrictions on patenting pure mathematical methods, as described further below.

(2) The second type relates to new ways of generating a training set or training a model. Often these are crucial considerations with health data where the lack of high quality data sets precludes high quality predictions and may require novel techniques to maximise the value of small or lower quality data sets.

(3) The third and most relevant category is the use of AI as a tool, i.e. the application of ML models to solving a particular healthcare problem. This is by far the most frequent type of AI invention we see, where the inventors have deployed a, usually known, type of ML model to a new type of data to make predictions, for example the application of a known convolutional neural network architecture to processing a new type of image data to make a diagnosis prediction.

In our experience, this point is often not well understood and worth emphasising: You do not need to have developed a new type of ML model to meet the requirements of patent protection – applying a known model in a new way, to a new type of data or to solve a new problem is the most common type of AI invention that is patented.

How does the patent office assess whether an AI-driven HealthTech technology is patentable?

An AI innovation must firstly meet the same requirements as any other type of invention:

- The innovation must be new: the first and lowest bar to overcome is that the innovation must have at least one new feature over the closest technology that is known, often referred to as the “prior art”.

This simply requires an application to claim a single difference between the innovation and the prior art.

- The innovation must be inventive: the new features must contribute to solving some kind of problem in an arguably “non-obvious” way.

Innovators are not always best placed to judge whether their own innovations are inventive. What seemed in retrospect a relatively straightforward change in a training method, preparation of input data or selection of features to obtain improved prediction results may well be considered an inventive step by the patent office.

If you have had to overcome some kind of technical problem when implementing your new technique, whether this relates to the preparation of appropriate training data, deciding on the model architecture and training method or how the trained model is applied – or even identifying a previously unrecognised healthcare problem to be solved – this is likely to be indicative of an inventive step

The patent office assesses what is obvious through the eyes of the fictional “skilled person” who has knowledge of the state of the art in the specific field but has no inventive capability whatsoever. In contrast, innovators in this area are generally problem solvers by nature, who frequently combine ideas from different fields and try new modifications to obtain improved results and so may not recognise what meets the “non-obvious” criteria.

In general, if you have had to overcome some kind of technical problem when implementing your new technique, whether this relates to the preparation of appropriate training data, deciding on the model architecture and training method or how the trained model is applied – or even identifying a previously unrecognised healthcare problem to be solved – this is likely to be indicative of an inventive step

- The innovation must not relate to excluded subject matter: broadly speaking, the new features and the problem they solve must be considered “technical” and not fall within one of the categories the patent office exclude from patentability.

The third requirement is the most opaque to those new to the patent system and is one responsible for many of the misconceptions around protecting AI inventions. Essentially, this means that your innovation must be applied to a “technical” problem, that is, not one that falls within the patent office’s categories of non-patentable subject matter.

The important point is that to be considered technical, the innovation must be tied to a “real-world” impact beyond the algorithm, whether this is the healthcare problem it seeks to solve or an impact in terms of improved functioning of the hardware used to run the algorithm.

A particularly relevant example of such a category is innovations that are considered purely an abstract mathematical method. Clearly, every ML innovation is, fundamentally, a mathematical method, leading to some of the misconceptions around difficulties in patenting these technologies. The important point is that to be considered technical, the innovation it must be tied to a “real-world” impact beyond the algorithm, whether this is the healthcare problem it seeks to solve, or an impact in terms of improved functioning of the hardware used to run the algorithm.

Another relevant example of a category of excluded subject matter is where the problem solved by the innovation is considered an administrative or business task. An AI innovation could be considered non-technical if the problem relates to applying your ML model to classify patient data records or select a health care plan from a number of options where the same model could be applied to any type of abstract data records and it is not specifically tied to the medical application.

Although there are categories of “non-technical” subject matter to be aware of, it is important to stress that generally, the patent office looks favourably on the application of AI to problems in HealthTech. The EPO explicitly provides a number of examples of inventions targeting such problems which are considered technical (i.e. not pure mathematical methods), for example:

- “controlling a specific technical system or process, e.g. an X-ray apparatus”

- “providing a medical diagnosis by an automated system processing physiological measurements”

- “the use of a neural network in a heart-monitoring apparatus for the purpose of identifying irregular heartbeats”

- “classification of digital images, videos, audio or speech signals based on low-level features”

Generally speaking, if the problem you are solving with your AI innovation one is specifically linked to a healthcare related application – for example by virtue of being applied to medical data, controlling equipment, monitoring or diagnosing a health condition, or even providing therapy in the case of digital therapeutics – then this will almost certainly be considered to fall within technical, patent eligible subject matter.

Practical summary for HealthTech innovators on identifying their AI inventions

In order to identify potentially patentable inventions at an early stage you should firstly have an understanding of the state of the art in the field – is anyone else solving a similar problem and how are they doing it? If your AI innovation has new features that solve a problem in that state of the art, and this problem is directly linked to the medical or healthcare application (rather than being generally applicable to any type of data), then this is a very good indication of patentability. There are, of course, always exceptions and borderline cases and your IP advisor will be able to confirm your thinking.

Is patent protection the right option?

The above framework can be used to take the first steps to identify patentable inventions within your technology. However, it is essential to consider whether patent protection is the right option for the particular technology and business plan. For example, an innovation that relates solely to details of a backend algorithm may be better protected as a trade secret if identifying infringement of the patent would be impossible and given that filing an application would require you to disclose details that may otherwise be kept secret. The right option will depend on a number of factors, such as how broadly the invention can be claimed, the business model and how the technology will be implemented and any plans to disclose through other means, such as academic journals. The key point is that the decision needs to be considered within the context of the overall IP strategy and it is these considerations that we explore in the second part of our IP series.

This article is aimed at the relative newcomer to the patent system. For IP practitioners and those with more experience, we provide an in-depth analysis of the considerations in preparing applications in this area in our Primer on AI and Patents. Please get in touch to obtain a copy, you can find my contact details here or contact us at gje@gje.com.