On Wednesday 5th June, Gill Jennings & Every hosted an event to investigate how Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are transforming digital healthcare and pharmaceuticals. We brought together an expert panel to help us find out more about the different ways AI is being implemented and their advantages and drawbacks. Each panellist has first-hand experience of AI in healthcare and pharmaceuticals, although approaching the topic from very different perspectives:

- Dr Mark Rackham, VP Chemistry at BenevolentAI – a market leader that has successfully raised $202 million in capital to fund its research

- Dr Rebecca Todd, Investment Director at Longwall Ventures – which invests in innovative, UK based, early stage companies in the healthcare, science and engineering sectors

- Dr Heather Rose, a Research Fellow at Birmingham University’s Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences and on the Children’s Brain Tumour Research Team at Birmingham Children’s Hospital

- Peter Finnie, Partner at Gill Jennings & Every, who chaired the discussion

Applications of AI in Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare

Where AI has useful applications, and where it does not, is a question that faces all industries. During the panel, Dr Rackham provided an eloquent rule of thumb for where AI can be useful – “AI is good for anything that is easy to do inside your head, but difficult to do with a mathematical equation”. For example, a human can easily distinguish visually between a dog and a cat, but it is incredibly hard to write a mathematical equation to do the same job. This is where AI could be implied.

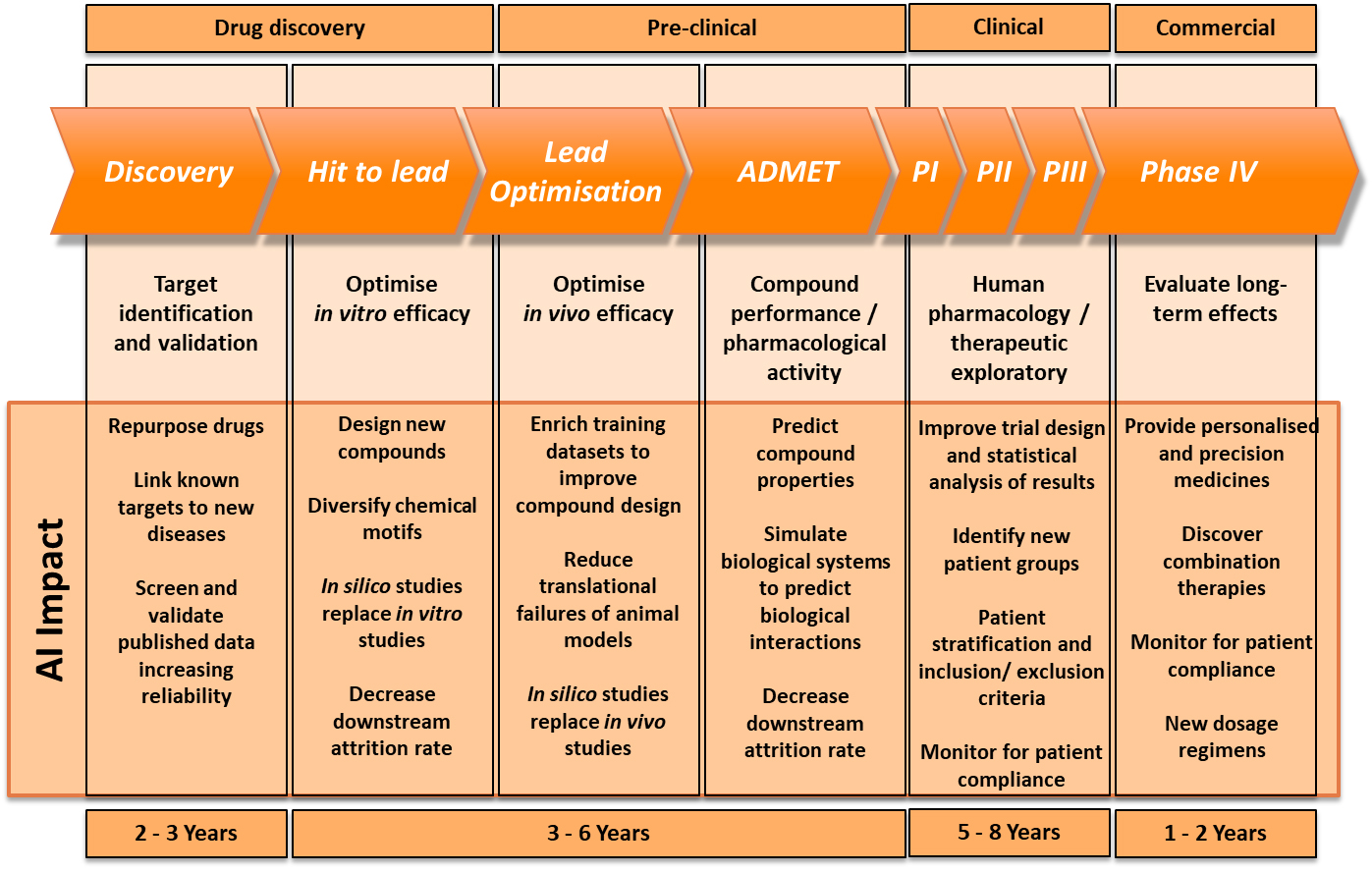

Indeed, this is how Dr Rose is looking to apply AI by examining MRI images to achieve a definitive diagnosis, which is critical for determining what treatment would be the most effective in the brain tumour trials her team is working on. For Birmingham Children’s hospital, AI is helping to overcome a major problem: that you can’t have personalised medicine without a certain level of diagnosis. It is using AI to assist in classifying the tumours and identifying important additional information required in a way that highly trained clinicians could not, to acquire a finely tuned diagnosis. This is vital to enable maximum effect during Phase IV of the pharmaceutical pipeline, such as providing precision medicines, monitoring for patient compliance and finding new dosage regimens.

Like Dr Rose, BenevolentAI has also been looking at utilising AI to classify existing patient data with the aim of finding new patterns, helping to understand diseases better and, therefore, find better treatments for different variations of diseases. Dr Rackham describes this as one of the most exciting applications of AI in the pharmaceutical sector.

The Benevolent AI team has explored a number of other avenues and applications for AI and ML in the five years since the company’s launch. They first used Natural Language Processing to ingest vast amounts of clinical literature – far more than a team of scientists could ever read – to uncover fertile areas of research to be explored. It has also been working on target ID, using AI to identify possible chemical compounds for certain diseases to accelerate the drug discovery stage.

Longwall Ventures has seen many “drug discovery enabler” start-ups in recent years, i.e. companies looking to bring AI technology to the likes of big pharma. However, Dr Todd is also interested in companies who are applying AI on the other side of pharma, such as in commercial applications at the end of the pipeline and to improve the marketing of drugs.

Challenges of AI in Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare

As with any new technology, there are always hurdles to overcome and pharmaceuticals is a more complicated industry than most to disrupt.

One issue that was identified across the board is the challenge of obtaining quality clinical data to train AI. For Dr Rose, who is researching a relatively rare condition in paediatric patients, availability of MRI scans is an issue, and the team engages across borders to try and pool as much data as possible to feed the AI software. In other trials, teams have gone so far as to generate synthetic scans to teach the AI algorithm, but Dr Rose emphasises the importance of having a strong core sample to base these extrapolations on.

Even in larger clinical trials, finding the appropriate data source remains a problem because diseases are an outlier and, while the AI can become very good at identifying “normal,” it is often more unreliable in identifying “abnormal”. As a result, Dr Todd often sees companies emphasise that their data is from the “world leading clinic in X disease”. However, Dr Todd says she is sceptical of companies who put too much emphasis on access to unique data sets because, as a unique selling point, this is hard to protect. In theory, any company could get access to the same or equivalent data set, so Longwall Ventures is much more interested in what the company is doing with the datasets and how that is protected.

How far can the machine go?

With these limitations in mind, the consensus was that the applications of AI have to be viewed realistically and, for now, could only be used to prompt scientific discovery, rather than lead it. For example, all of the panellists agreed that – at least in the near future – in silico data would not replace in vitro or in vivo studies in the pre-clinical stage of the pharmaceutical pipeline during which scientists are optimising in vivo efficacy. Thus, running these trials in a computer program will not be considered an acceptable substitute for existing animal studies and clinical trials, so they cannot radically fast track the pre-clinical and clinical stages of the pharmaceutical pipeline.

Dr Rackham described a psychological hurdle that needs to be overcome first. Similar to self-driving vehicles, humans are less comfortable with machines making life-changing decisions on their behalf, despite the fact that statistically an AI algorithm is less fallible than a human doctor. While questions remain over the data AI uses, and how to regulate algorithms that are potentially ever-evolving, there will be limitations on what decisions people will accept from the technology that it makes independently.

However, that is not to say AI doesn’t have a role to play in the pharmaceutical pipeline. At the beginning of the timeline in the drug discovery phase, companies such as BenevolentAI have seen great success with AI flagging patterns and suggesting solutions to clinicians that they almost certainly would not have seen themselves. This particularly assists with repurposing new drugs and linking known targets to new diseases. During the hit to lead stage of drug discovery, AI could narrow the infinite possibilities of a chemical compound for a new drug down to a handful, or highlight specific functional groups that are necessary in the compound, for a pharmaceutical company to explore, which is already delivering huge efficiency savings.

The panel was in agreement that empowering healthcare professionals with the intelligence generated by AI is where the immediate benefits of the technology lie, and that the combination of people and AI can achieve much greater than either individually.

IP considerations

For Longwall Ventures, one of the biggest considerations before investing into an AI company is whether its innovation is protectable. The IP of the company is the biggest contributor to the underlying value because it is the only thing stopping another company from copying them and doing the same thing.

However, securing a patent for AI technology is not simple. Software is excluded from being patentable in the UK unless it has a “technical effect” – i.e. changes the function of the computer, which most AI software does not. Furthermore, even when a patent for the AI is possible – for example if the company invents a unique AI training method – it may not be in its interest to file, as this places the method in the public domain.

Consequently, AI developers such as BenevolentAI have typically focused their IP strategies on the outcomes of the AI implementation, rather than the AI itself. The chemical compounds that are created, partly as a result of AI intervention, are protectable – and are seen as the “currency of success”.

Of course, if AI does ever take the final step to be feasibly considered “the inventor,” that could open up a whole other can of worms in terms of inventorship and ownership of patent rights. But today, companies using AI as a facilitator for innovation are reaping the benefits of a faster route to market for potentially life saving breakthroughs, and are able to protect their outputs.

If you would like to find out more about IP strategies for AI in pharmaceuticals or more broadly in the life sciences sector please contact gje@gje.com.